The Valley of Queens

Embark on a journey through space and time With Royal Black Tours to the Valley of Queens, which was the resting place for Ancient Egyptian Queens, Princesses, and Princes. Its ancient name was Ta-Set-Neferu which in ancient Egyptian language means (The Place of Beauty) or (the Place of the Royal Children).

about the Valley of Queens?

The Valley of the Queens encompasses various sub-valleys, including the Valley of Prince Ahmose, the Valley of the Rope, the Valley of the Three Pits, and the Valley of the Dolmen, in addition to the main wadi. While the main wadi hosts 91 tombs, the subsidiary valleys contribute an additional 19 tombs, all dating back to the 18th Dynasty.

The specific rationale behind selecting the Valley of the Queens as a burial ground remains uncertain. Factors such as its proximity to the workers’ village of Deir el-Medina and the Valley of the Kings might have influenced the decision. Additionally, the presence of a sacred grotto dedicated to Hathor near the valley entrance could have played a role, potentially associated with beliefs in the rejuvenation of the deceased.

Recognizing its cultural significance, the Valley of the Queens, along with the adjacent Valley of the Kings and Thebes, was included in the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1979.

A short take about the valley of queens

18th Dynasty

In the Eighteenth Dynasty, the Valley of the Queens witnessed the earliest construction of tombs, notably that of Princess Ahmose, daughter of Seqenenre Tao and Queen Sitdjehuti, likely erected during the reign of Thutmose I. Alongside royalty, individuals from the nobility, such as a stable head and a vizier, were laid to rest in this area.

The tombs in the Valley of the Three Pits, primarily dating from the Thutmosid period, are labeled from A to L. This valley is distinguished by its three shaft tombs, now known as QV 89, QV 90, and QV 91, hence its name.

Traveling through the Valley of the Dolmen, one follows an ancient route once frequented by workers commuting from Deir el-Medina to the Valley of the Queens. Along this path stands a small temple carved from rock, dedicated to Ptah and Meretseger.

Tombs from this period typically exhibit modest designs, consisting of a chamber and a burial shaft, with some expanded to accommodate multiple burials. Among those interred are royal offspring and esteemed individuals of nobility.

Within the Valley, a tomb known as the Tomb of the Princesses, dating to the era of Amenhotep III, yielded artifacts now showcased in museums. These artifacts include fragments of burial items belonging to various members of the royal household, such as a canopic jar fragment bearing the name of King’s Wife Henut, enclosed in a cartouche. Other discoveries feature canopic jar fragments inscribed with the names of Prince Menkheperre, King’s Great Wife Nebetnehat, and King’s Daughter Ti, all from the mid-18th Dynasty.

19th Dynasty

During the 19th Dynasty, there was a shift towards more selective use of the Valley. Tombs from this era were exclusively designated for royal women. Among those interred were many esteemed wives of Ramesses I, Seti I, and Ramesses II. Notably, Queen Nefertari’s resting place, carved meticulously into the rock (1290–1224 BCE), stands out with its well-preserved polychrome reliefs. While royal family members continued to find their eternal abodes in the Valley of the Kings, Tomb KV5, housing the sons of Ramesses II, exemplifies this tradition.

Queen Satre’s tomb (QV 38) is believed to be among the earliest prepared during this dynasty. Its construction likely began in the reign of Ramesses I and concluded during the reign of Seti I. Some tombs were initially prepared without a specific owner in mind, with names added upon the passing of the royal female.

what are the tombs that I shouldn’t miss?

The Valley of queens is mostly overshadowed by the valley of kings due to the many factors; however, that doesn’t mean that the valley of queens has anything short of absolute beauty and everlasting cultural significance ad we will share with you our personal favorites.

Queen Nefertari

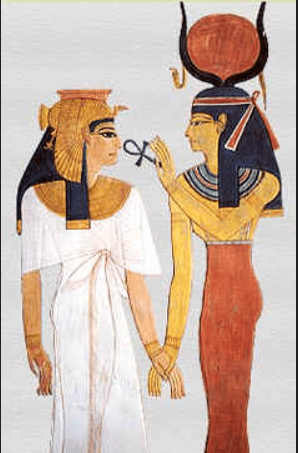

Nefertari, also referred to as Nefertari Meritmut (Lady of The Two Lands,

Mistress of Upper and Lower Egypt), held the esteemed position of being the first Great Royal Wife of Ramesses the Great, an eminent figure in Egyptian history. Renowned alongside notable queens like Cleopatra, Nefertiti, and Hatshepsut, she remains one of the most recognized figures, despite not being acknowledged for reigning independently.

Gifted with a rare education, she possessed the ability to both read and write hieroglyphs, a remarkable skill for her time. Utilizing her talents, she engaged in diplomatic affairs, corresponding with other influential royals. Her opulently adorned tomb, QV66, stands as one of the grandest and most magnificent within the Valley of the Queens. Additionally, Ramesses honored her by erecting a temple for her at Abu Simbel, adjacent to his colossal monument, hoping to immortalize his queen for all eternity.

Tomb of Amenherkhepshef

Situated in the Valley of the Queens, nestled on the western bank of the Nile River in Luxor, Egypt, lies the tomb of Prince Amenherkhepshef. This royal figure lived during the 19th Dynasty of the New Kingdom era, approximately around 1250 BCE. As the offspring of Pharaoh Ramesses III and Queen Tiye, his life was tragically cut short at a tender age.

Within this tomb, intricate scenes from the Egyptian Book of the Dead adorn the walls, capturing glimpses of Amenherkhepshef alongside his parents and other relatives. However, what truly sets this tomb apart are its vibrant and remarkably preserved paintings. These artworks offer valuable insights into the spiritual beliefs of ancient Egypt during the New Kingdom epoch. They chronicle the prince’s passage into the afterlife and depict the sacred rituals associated with burial, providing a fascinating window into this bygone era. Fair warning though this tomb is considered the farthest in the valley

Tomb of Prince Kha Em Wast

The tomb of Prince Kha Em Wast stands out as a gem in the Valley of the Queens, boasting unparalleled artistry and vibrant colors, second only to Nefertari’s tomb.

While many walls are covered with floor-to-ceiling glass, the artwork remains distinctly visible, allowing visitors to appreciate its beauty.

Prince Kha Em Wast, a son of Rameses III, met a premature demise, adding to the tragedy of his short life. Believed to be Rameses III’s eldest son, he held the esteemed position of high priest of Ptah in Memphis. However, despite his lineage and prestigious role, he did not ascend to the throne upon his father’s passing. Instead, the kingship passed to Rameses III’s brother. Egyptologists remain puzzled as to why Prince Kha Em Wast was overlooked for his uncle in the succession.